‘We called her mastodon’: infamous New Orleans

orphanage’s abusive history ran deeper than ever known

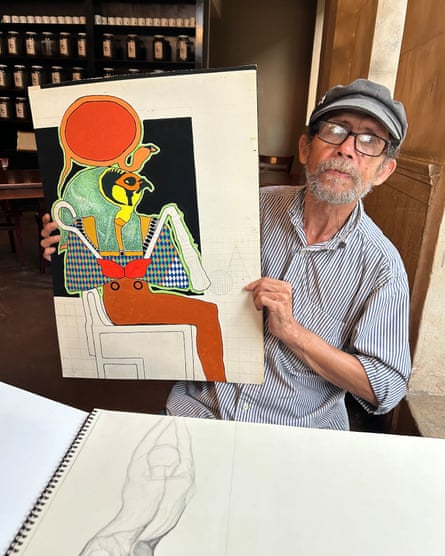

Geo, the name he prefers, sits in a coffee shop on a rainy afternoon as streetcars clang along outside. He is 64. He arrived at Madonna Manor, the Catholic orphanage he is now suing, in August of 1967, as a ward of Louisiana, age seven.

“My childhood was horrific,” he says matter-of-factly. “My father was an abusive alcoholic, my mother diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenic. Madonna Manor was a place where dysfunctional parents dumped their children. My mom was subject to electroshock therapy and thorazine. She lost a baby. She had a psychotic breakdown and was placed in a mental hospital. The state took me over.”

Thin, bearded, redolent of nicotine, he holds a sketchbook of his works.

He enjoys the fellowship of a drawing class once a week, sketching figures of live models. Alcoholics Anonymous helps too, he says, adding: “I have been sober since 30 May and intend to go a long way sober.”

Existing on a disability check and earnings from his sporadic art sales, Geo lives on one side of the shotgun-style house where he grew up. His brother, a survivor of the same orphanage, lives on the other side. Neither man has children.

Madonna Manor and its sister facility, Hope Haven, occupy Spanish mission-style buildings on opposite sides of Barataria Boulevard in the New Orleans suburb of Marrero.

From the time he entered the now-shuttered complex, says Geo, the “sexual and physical abuse was constant”.

Sister Martin Marie was “a huge, ugly, mean woman we called Mastadon behind her back”, he said of a nun who worked there. “The nuns had a sadistic streak. Martin Marie liked to whip out a fold-out army shovel and beat us.”

He sips from a cappuccino sitting next to his sketchbooks.

“She was famous for grabbing and abusing us for sexual pleasure. A lot of these women – those nuns – had severe problems,” he adds.

Charles Earhardt, a bus driver and volunteer presence at the home, began molesting Geo immediately after the boy arrived, he says. Earhardt, named by several other survivors as a pedophile, was dismissed from his duties. Yet somehow he managed to adopt two boys – and, in short order, abused them, too, according to documents produced during a memorandum that led to a $5.2m settlement between the church and orphanage abuse claimants.

The Guardian gained access to that memo, written by the attorneys Frank LaMothe, Roger Stetter and Michael Pfau – the representatives of 18 orphanage victims – to a court-approved mediator also working with lawyers for the Roman Catholic archdiocese of New Orleans and Catholic Charities, which oversaw Hope Haven and Madonna Manor.

The memo not only contains that incomprehensible revelation about Earhardt. It also makes clear that there were more abusers – and more victims – than ever known at two orphanages that have come to embody the scourge of clergy molestation in south-east Louisiana.

An institution out of control

The sheer scope of the institutional sexual abuse that the Catholic church in New Orleans concealed at the orphanages alone beggars belief.

“The institution was … out of control, had no safeguards to protect the children, and was a haven for pedophiles,” wrote LaMothe, Stetter and Pfau in a 2009 report to the mediator helping them negotiate with the church attorneys.

Earhardt is now dead. So is Sister Martin Marie and seven other nuns accused of physical and sexual abuses while Earhardt and 13 other male predators sexually traumatized boys at the orphanages, according to the narrative in the settlement memorandum, anchored in files that church attorneys provided in the discovery phase of the litigation.

Please continue reading on the Guardian at:

A New Orleans archdiocese spokesperson

No comments:

Post a Comment